I could see my breath as I stepped into the bathroom, and shuddered at the thought of taking off any of my layers (let alone all of them) to bathe. But I needed to, I wanted to…even though I didn’t. The hot water caused my skin to steam, even as I soaped and shampooed and filled the bathroom with such a thick haze that I could barely see my feet. Isn’t winter fun? I stepped out and hastily toweled my hair, ever the more thankful that I had finally gone ahead and cut a good six inches off. Actually, one of the other volunteers did the cutting, probably the first home haircut I have had since I was six or seven years old. It looks quite nice and even more important, I didn’t have to feel it wet and cold down my back as a struggled to get dressed enough to move back into the warm part of the house.

Last night we headed up to the village above Vayk. This is the village my host mother and father grew up in, as well as my counterpart. The small car was to come at 6, and at 6:30 we all piled in—7 full grown adults and a toddler. The ride up was more pleasant than the ride down, me with a headache, crammed into the back seat with three other woman and the squirmy toddler, who had entirely too much chocolate (and a little vodka, licked off of fingers), my host father in the passenger seat, with his nearly six foot tall son in his lap, very drunk and talkative, and the driver who kept stopping for various reasons…to chat, to look at the city in the dark and so on. At least, I reasoned, if we were to get an accident, it is very likely that it would be physically impossible for me to move, let alone get thrown though the windshield or something. This was comforting.

Still, I am settling into my life here, and things seem normal. I realize I crave things, not because they don’t exist in this country, but simply because they exist in this family. Simple things that remind me of home, but are beyond the means of this simple life. These people are isolated from the rest of the country, the part with wealth, and it is easy to forget about each respective world when living in the other. It is easy to forget that I view 1000 dram (about 2 dollars) in a starkly different way than the vary family that I live with. I enjoy the simplicity but I miss the freedom that seems to be mutually exclusive when living with a family, even one was wonderful as my own.

I have finally summoned the courage to begin making my own breakfast (oatmeal…extravagant I know, but better than bread), after battling fears of insulting them, shaming them, or embarrassing myself. I have done quite a bit of the latter, which I am much easier able to accept than the former…I have had quite a bit of practice at this point. Still, I look forward to the day when I don’t have to sneak around making oatmeal when the family isn’t home so as to perfect my technique to avoid eliciting the much unwelcome “help.”

Freedom will increase and my health will certainly improve with some control over my diet, and over all I think I will be happier, but I will also very much miss this family. I catch myself often nowadays in some sort of a waking daydream mixed with reminiscence. It is as if I briefly forget that I am not at home. I am sitting here and it is finally warm, the new heater silently casting blue light and much welcome warmth throughout the living room, and we have just moved Gevorg’s bed in here (he sleeps in the warm room in winter), and Gero and Alvard and watching television, and tea is boiling on the stove, and things seem normal. Like next week will be Christmas break and we will put up the tree and make cookies and bake a ham. But it isn’t normal. There will certainly be no ham, and all my interactions are in Armenian, and the television is speaking Russian, and my sheets are dirty because I don’t know how to wash these giant things by hand in a tiny little plastic basin, and the family is taking their weekly bath (if that often for some of them), and we just had beet soup for dinner. But it still feels like home. And that is the bottom line. And I am really, truly learning the meaning of home and family, and it doesn’t have anything to do with the building or the city, or even the country, and blood relations don’t really matter in the end. I have lost quite a bit of independence (although I have gained a considerable amount since PST if that tells you anything), but this time I consider it to be a worthwhile trade, at least for a while. My language, my cultural knowledge, my ability to eat strange meat, my confidence….these things have all improved while living here. We don’t always understand each other, in fact we often don’t understand each other, but we laugh and laugh, and dance and sing, and eat and drink, and badger and pester, and laugh some more, and slowly I feel a part of something bigger than me, more important than me, and ultimately representative of my mission here in the first place.

Sunday, November 13, 2005

My muscles are sore, and although it hurts to move my head around too fast, or to lift my arms, I am happy because I know I have done something. I don’t think the Armenians really understand sore muscles—they would probably be busy smearing yogurt all over the skin, soaking bandages in vodka, and drinking tea. I, on the other hand, know the true cause—productivity. A day of working at a Habitat for Humanity site in a nearby village. Although my work consisted of merely passing metal buckets full of rocks down an assembly line (a full discourse on Armenian building techniques to come later…), for the first time, I felt that I was really doing something useful. An important project, with a tangible project at the end—a house.

Certainly this is important, but the reality is that truly any Armenian over the age of six could be doing the work I was. There is no reason for me to fly half-way around the globe to pass buckets in someone else’s country—at this point there is more than enough work of this type at home (unfortunately). The difference, or what makes the difference, is that volunteerism is a foreign concept here (literally in many cases…). The importance of my work lay not in the actual house, although the home-owners were certainly grateful, but instead in lay in the example we set as Americans in our willingness to help, to perform hard, physical labor, simply because we want to help and feel that is the right thing to do. More and more I see that the best thing I can do here is teach the Armenians how to help themselves, they have the resources, they just need to figure out how to work together for the greater good, to rearrange their thought patterns, and to exchange complacency for self-directed betterment.

Sometimes our American ideals get the better of us, plunging us into greed and gluttony, but it is there same values—hard work, efficiency, independence, strength of character, resolve, desire to improve, initiative, that have so quickly launched our country to the powerful leadership position it is in. Perhaps now we find ourselves with too much of a good thing in terms of the state of our international affairs (I am still somewhat connected via Newsweeks and news in Russian—the former more helpful than the latter). Simultaneously I find myself in a place with too much of a different style of government.

One of the best things we are doing right now is encouraging young Armenians to get involved in their communities and to begin volunteering their time towards productive entities. Rapid change in a country like Armenia can be good and bad—we have to try to steer the urban explosion and mass migration to Yerevan back towards the good end of the spectrum. I am pretty sure the only way to do this is to make other places in Armenia appealing in terms of a place to live rather than a place to escape from.

Yesterday the volunteers (peace corps) outnumbered the Armenians, but there was a small showing from the local university, and we did our best to make it a fun day in hopes that these few students would spread the word. Habitat for Humanity Armenia, is a little different from that in the US (as you might imagine). Instead of starting from scratch, they use housing structures that already exist…there are lots of shells of houses to choose from, salvage what they can, and rebuild the rest. This means that houses can be built relatively inexpensively (by US standards anyway), often a “new” home is finished for $5000. Of course, all of the typical Armenian building techniques are employed—cement floors, single pane glass windows, no insulation (I must be thinking about the cold). And hence, the buckets of rocks--we filled the entire house with a layer of large gravel, upon which the cement will be poured.

Meanwhile I have managed to get involved in a few other micro-projects and I learning more about what I need to do here and how I can possibly go about doing it. Some of this has come through deeper interaction through my Armenian friends (who speak English and thus enable me to have a conversation of some depth). I have spent some time with some of my LCF’s in Yerevan, and interacting with them outside of PST, in what constitutes their day-to-day life had been enjoyable and educational. It is nice to be able develop friendships with host country nationals on this level. These, however, are people who are used to working with American, who understand the Peace Corps very well, have traveled outside of Armenia themselves, and who in general, have a positive outlook for the future of their country. They are certainly the exception rather than the norm.

Through these LCF’s I have had the opportunity to work with some English language clubs in Yerevan, and to actually teach a lesson on the environment for one of the clubs. Due to the fact that an American was coming, 44 students, ages 17-18 showed up for the lesson (I was told “I don’t know how many, but probably more than 20”) more than 20 indeed. Fortunately, we were able to start with a 30 minute question and answer session about why I was in Armenia, what I think about the country and what exactly I am doing here. I am not sure of all the answers myself, but I guess I made stuff up pretty well. Then we discussed the environmental problems of Armenia (there are many) and what we can do about them as individual citizens.

This group of students taught me about the way their generation thinks about Armenia and about the problems that plague their country. There is an obvious recognition of the problems, but also an underlying resignation to the inability to do anything about it. How can I give these kids hope while at the same time instilling the message that they are the hope? I did my best to convey this message and provide some optimism (although one of the two male students in the room did his best to do the opposite). I am planning to go back in the future to do more lessons with this group and hope to bring them information about places where they can get involved and hopefully impel them to do so.

Certainly this is important, but the reality is that truly any Armenian over the age of six could be doing the work I was. There is no reason for me to fly half-way around the globe to pass buckets in someone else’s country—at this point there is more than enough work of this type at home (unfortunately). The difference, or what makes the difference, is that volunteerism is a foreign concept here (literally in many cases…). The importance of my work lay not in the actual house, although the home-owners were certainly grateful, but instead in lay in the example we set as Americans in our willingness to help, to perform hard, physical labor, simply because we want to help and feel that is the right thing to do. More and more I see that the best thing I can do here is teach the Armenians how to help themselves, they have the resources, they just need to figure out how to work together for the greater good, to rearrange their thought patterns, and to exchange complacency for self-directed betterment.

Sometimes our American ideals get the better of us, plunging us into greed and gluttony, but it is there same values—hard work, efficiency, independence, strength of character, resolve, desire to improve, initiative, that have so quickly launched our country to the powerful leadership position it is in. Perhaps now we find ourselves with too much of a good thing in terms of the state of our international affairs (I am still somewhat connected via Newsweeks and news in Russian—the former more helpful than the latter). Simultaneously I find myself in a place with too much of a different style of government.

One of the best things we are doing right now is encouraging young Armenians to get involved in their communities and to begin volunteering their time towards productive entities. Rapid change in a country like Armenia can be good and bad—we have to try to steer the urban explosion and mass migration to Yerevan back towards the good end of the spectrum. I am pretty sure the only way to do this is to make other places in Armenia appealing in terms of a place to live rather than a place to escape from.

Yesterday the volunteers (peace corps) outnumbered the Armenians, but there was a small showing from the local university, and we did our best to make it a fun day in hopes that these few students would spread the word. Habitat for Humanity Armenia, is a little different from that in the US (as you might imagine). Instead of starting from scratch, they use housing structures that already exist…there are lots of shells of houses to choose from, salvage what they can, and rebuild the rest. This means that houses can be built relatively inexpensively (by US standards anyway), often a “new” home is finished for $5000. Of course, all of the typical Armenian building techniques are employed—cement floors, single pane glass windows, no insulation (I must be thinking about the cold). And hence, the buckets of rocks--we filled the entire house with a layer of large gravel, upon which the cement will be poured.

Meanwhile I have managed to get involved in a few other micro-projects and I learning more about what I need to do here and how I can possibly go about doing it. Some of this has come through deeper interaction through my Armenian friends (who speak English and thus enable me to have a conversation of some depth). I have spent some time with some of my LCF’s in Yerevan, and interacting with them outside of PST, in what constitutes their day-to-day life had been enjoyable and educational. It is nice to be able develop friendships with host country nationals on this level. These, however, are people who are used to working with American, who understand the Peace Corps very well, have traveled outside of Armenia themselves, and who in general, have a positive outlook for the future of their country. They are certainly the exception rather than the norm.

Through these LCF’s I have had the opportunity to work with some English language clubs in Yerevan, and to actually teach a lesson on the environment for one of the clubs. Due to the fact that an American was coming, 44 students, ages 17-18 showed up for the lesson (I was told “I don’t know how many, but probably more than 20”) more than 20 indeed. Fortunately, we were able to start with a 30 minute question and answer session about why I was in Armenia, what I think about the country and what exactly I am doing here. I am not sure of all the answers myself, but I guess I made stuff up pretty well. Then we discussed the environmental problems of Armenia (there are many) and what we can do about them as individual citizens.

This group of students taught me about the way their generation thinks about Armenia and about the problems that plague their country. There is an obvious recognition of the problems, but also an underlying resignation to the inability to do anything about it. How can I give these kids hope while at the same time instilling the message that they are the hope? I did my best to convey this message and provide some optimism (although one of the two male students in the room did his best to do the opposite). I am planning to go back in the future to do more lessons with this group and hope to bring them information about places where they can get involved and hopefully impel them to do so.

Wednesday, November 09, 2005

Ararat Dreams

The sun rose spectacularly this morning, casting the clouds in brilliant shades of red, orange and purple… The rolling hills of desert and stark land formations staunchly contrasted the colors of the morning sky. I watched the scene unfold from the back window of a marshutnie as we stiffly bounced along scantily paved highways, plowing our way through the occasional herd of farm animals—sheep, goats, cows, old Armenian men with sticks, who vaguely alternated between chasing their charges off the road in the face of oncoming traffic, and idly chattering about whatever shepherds have to chat about in the early morning chill.

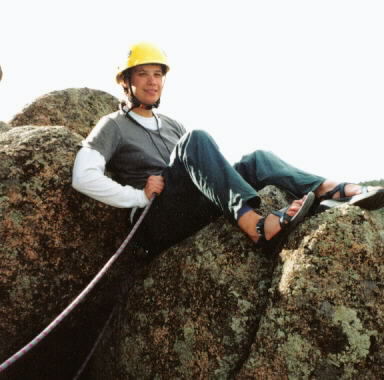

As I was contemplating the subject matter of Armenian shepherd conversation, my eye was caught by a break in the sun-bathed clouds. There, in the distance, stood the newly snow-covered flanks of Mt. Ararat, magnificently aglow in a burning shade of yellowish orange. The scene was startlingly crisp, and sent a small chill down my spine—half out of sheer the awe, the other the return of the itch to climb. To experience, first-hand, the cold searing my lungs, the ice crystals stinging my face, the morning sun creeping through the shadows, turning the ice crust into soft, wet mush. Communing directly with nature and thus feeling directly its brutality and harsh realities somehow makes it that much more beautiful.

The two white cones dominated the landscape—the large monstrosity and the smaller replica, rising serenely above the cloud layer, basking in the rising sun. It was one of those scenes that resonates in memory, that can be matched by something different, perhaps, but never replicated. That, in one simple glance, defies those who lack appreciation and understanding, and for the rest of us, creates an excitement about the natural world that can only be quelled through direct interaction.

Perhaps I will never again see Ararat in today’s glorious form. I have no pictures to commemorate the event—they would have merely distracted from the experience anyhow. Only a memory sharply etched into my mind as tangible proof of creations true glory.

Nature is a strange entity—separate in its existence from our day-to-day lives, and yet intrinsically and inextricably intertwined in everything that comprises the amalgamation of civilization. At its gentlest it is a time-marker, ticking off the years in snow accumulation and thaw, autumn color changes, spring blooms and summer breezes, at its most menacing, a force well beyond the scope of human control. Perhaps a well-needed reminder of forces greater than ourselves and an opportunity for introspection towards the state of humanity. A poignant opportunity for selflessness and a simultaneous invitation to the malicious, but which prevails?

I find I am given the opportunity and the catalyst to contemplate such issues while in Armenia, where the snowfalls mark more than just passing time. They mark a time that is better than the last, but still not good enough. The snow-crested mountains signify the end of the canning season, the final harvest, the last chance for laundry to dry before it freezes. They signal the beginning of cold nights, poor nutrition, short days, layers of clothing, evenings passed drinking tea and huddling around the heater. An experience I am sure not to forget. Normally the new snow falls are exciting for me, but now they linger with a newfound sense of a dread, and perhaps a newfound sense of respect for the power of nature over the human condition. This time I can’t some home from my camping trip to a nice warm house and a long hot shower. I am living it, a two-year commitment regardless of the season and the lack of pizza delivery.

Saturday, November 05, 2005

Head Soup

What a week it has been. James left for America, and I was entrusted with the key to his apartment—and the responsibility of letting his land-lord’s wife in to clean, because (and I quote) “James doesn’t clean, his apartment is very dirty, but it’s okay…he’s a boy.” And so I sat, reading a book, listening to this woman shuffling around a muttering under her breath about the dust bunnies and filthy corners and the unswept floors. In addition to being the bearer of the key, I was also a translator of all things American. In her quest to find something to clean the bathtub with, she brought me sunscreen, odor eaters foot powder, cockroach traps, and shampoo. Not knowing the words for these items, I could only say “for the sun,” “for your feet,” “for big bugs,” and so on. I guess she eventually found what she was looking for.

No less that seven hours later, I was back home, feeling less than stellar. My plan was to eat and go to bed, but my stomach was not so excited about the eating part. After fending off pleas to eat more for several minutes, I broke down and said I was a little sick. There was some gasping and looks of panic, and then my host mother and father sprung into action, brining me blankets and pillows and tea and honey and jam and vodka. Yes, vodka. Vodka cures everything. I managed to get away with only one sip of the vodka, one spoonful of honey, one bite of quince jam and one cup of tea. Although, the tea conversation went something like this:

Gero (father): bring jill a cup of tea

Gero (a minute later): bring jill two cups of tea

Me: no, bring jill one cup of teaGero: bring jill two cups of teaMe: bring jill one cup of tea

Gero: bring jill three cups of tea

Me: bring jill one cup of tea

Gero: bring jill three cups of tea

I ended up with two cups of tea, although I was saved by my host brother, who came home also feeling sick. I gave him my second cup of tea and told him it was for him.

After answering repeated questions about why I was sick, where I got sick, when I got sick and whether I mersoomed (got cold), where I mersoomed, if there were windows open at James house, if I got sick at the Halloween party, if my bedroom wasn’t warm enough, and on and on, I went to bed and slept a good long time.

I woke up this morning feeling a bit better, although not one hundred percent, and went to the kitchen to make my breakfast. Where I was greeted by a tongue. A big, long, fatty tongue, sitting on the counter. I did my best to ignore it and continued making my tea. I was enjoying my tea, when I turned around to see my host mother roasting a head over the open flame of the burner. A big head--cow head I think. I tried not to look to close and decided this was cue to take my leave. We will be having Khash again soon, although this time instead of being hoof soup it is going be head soup. MMMmmmm.

The tongue, on the other hand, was served for lunch, in little tongue slices on a platter. I felt obligated to a least try one little tongue slice. I don’t like tongue. Later, I got the opportunity to try seom brain—served on a lisce of bread. Brain is kind of a browninsh paste, strange tasting and nopt really something I ever want to eat again, to be honest. At least I tried it. As I was leaving for yerevan this weekend, I got a peek at the still cooking khash (head soup, with vodka). My host mother lifted the lid of the pot for me to look, and there, sitting in the midst of boiling broth, was a giant skull. MMMmmm skull soup. I am happy to be Yerevan eating pizza, thanks.

I was thinking about all the strange encounters I have had while in Armenia the other day, and perhaps more importantly, about how normal these things have become. It makes me wonder what will happen when I get back to the states.

I was thinking that when I come back to America I will start chasing people down the streets and screaming their nationality at them, and perhaps, just for good measure, I will throw in a few other similar nationalities. For instance, I could be walking through campus and see someone from China—I would take off running behind them yelling “Chinese, Chinese, Chinese, Chinese,” and then maybe throw in “Japanese” every once in a while…just in case.

I also think that I will point to pimples and blemishes on people’s faces and ask “what is that?” And, if people are really lucky, and they have shown any sign of weight gain, I will tell them that they have gotten very fat. When I see people who I don’t know, or who are different than me, I will get right in their face…and stare. Intently, like I am examining a new specimen, or a species thought to be extinct. Then I will ask my friends questions about this person—in their presence as if they don’t understand what I am saying.

When my friends come over to my house, I will ask them if they would like something to eat. If they say no, I will pile huge helping of it on their plate and insist that they eat. If they tell me don’t want it, I will say “why? You don’t like it?” When I talk about people I know, I will refer to them as the “the fat one” or “the ugly one,” or whatever other defining characteristic they may have—nice or not.

On the other hand, I am getting used to being able to talk about how obnoxious a person is while they are standing a mere five feet away (or less). This is going to get me in trouble some day, I know it, but for now it is just so easy to turn to my fellow English speaking friends and say exactly what is on my mind. Of course, the Armenians often do this even when they are aware that you speak their language, so I suppose I shouldn’t be too concerned. What will I do in the US where people actually understand the things I am saying and I am expected to be polite? I am in trouble.

These things have just be come so indicative of life here that have begun to be an accepted part of the way I live. The best I can do is laugh…and write about it so you can laugh, and think that maybe someday there will have been enough foreigners in this country that we cease to be as curious of an object as we are now.

No less that seven hours later, I was back home, feeling less than stellar. My plan was to eat and go to bed, but my stomach was not so excited about the eating part. After fending off pleas to eat more for several minutes, I broke down and said I was a little sick. There was some gasping and looks of panic, and then my host mother and father sprung into action, brining me blankets and pillows and tea and honey and jam and vodka. Yes, vodka. Vodka cures everything. I managed to get away with only one sip of the vodka, one spoonful of honey, one bite of quince jam and one cup of tea. Although, the tea conversation went something like this:

Gero (father): bring jill a cup of tea

Gero (a minute later): bring jill two cups of tea

Me: no, bring jill one cup of teaGero: bring jill two cups of teaMe: bring jill one cup of tea

Gero: bring jill three cups of tea

Me: bring jill one cup of tea

Gero: bring jill three cups of tea

I ended up with two cups of tea, although I was saved by my host brother, who came home also feeling sick. I gave him my second cup of tea and told him it was for him.

After answering repeated questions about why I was sick, where I got sick, when I got sick and whether I mersoomed (got cold), where I mersoomed, if there were windows open at James house, if I got sick at the Halloween party, if my bedroom wasn’t warm enough, and on and on, I went to bed and slept a good long time.

I woke up this morning feeling a bit better, although not one hundred percent, and went to the kitchen to make my breakfast. Where I was greeted by a tongue. A big, long, fatty tongue, sitting on the counter. I did my best to ignore it and continued making my tea. I was enjoying my tea, when I turned around to see my host mother roasting a head over the open flame of the burner. A big head--cow head I think. I tried not to look to close and decided this was cue to take my leave. We will be having Khash again soon, although this time instead of being hoof soup it is going be head soup. MMMmmmm.

The tongue, on the other hand, was served for lunch, in little tongue slices on a platter. I felt obligated to a least try one little tongue slice. I don’t like tongue. Later, I got the opportunity to try seom brain—served on a lisce of bread. Brain is kind of a browninsh paste, strange tasting and nopt really something I ever want to eat again, to be honest. At least I tried it. As I was leaving for yerevan this weekend, I got a peek at the still cooking khash (head soup, with vodka). My host mother lifted the lid of the pot for me to look, and there, sitting in the midst of boiling broth, was a giant skull. MMMmmm skull soup. I am happy to be Yerevan eating pizza, thanks.

I was thinking about all the strange encounters I have had while in Armenia the other day, and perhaps more importantly, about how normal these things have become. It makes me wonder what will happen when I get back to the states.

I was thinking that when I come back to America I will start chasing people down the streets and screaming their nationality at them, and perhaps, just for good measure, I will throw in a few other similar nationalities. For instance, I could be walking through campus and see someone from China—I would take off running behind them yelling “Chinese, Chinese, Chinese, Chinese,” and then maybe throw in “Japanese” every once in a while…just in case.

I also think that I will point to pimples and blemishes on people’s faces and ask “what is that?” And, if people are really lucky, and they have shown any sign of weight gain, I will tell them that they have gotten very fat. When I see people who I don’t know, or who are different than me, I will get right in their face…and stare. Intently, like I am examining a new specimen, or a species thought to be extinct. Then I will ask my friends questions about this person—in their presence as if they don’t understand what I am saying.

When my friends come over to my house, I will ask them if they would like something to eat. If they say no, I will pile huge helping of it on their plate and insist that they eat. If they tell me don’t want it, I will say “why? You don’t like it?” When I talk about people I know, I will refer to them as the “the fat one” or “the ugly one,” or whatever other defining characteristic they may have—nice or not.

On the other hand, I am getting used to being able to talk about how obnoxious a person is while they are standing a mere five feet away (or less). This is going to get me in trouble some day, I know it, but for now it is just so easy to turn to my fellow English speaking friends and say exactly what is on my mind. Of course, the Armenians often do this even when they are aware that you speak their language, so I suppose I shouldn’t be too concerned. What will I do in the US where people actually understand the things I am saying and I am expected to be polite? I am in trouble.

These things have just be come so indicative of life here that have begun to be an accepted part of the way I live. The best I can do is laugh…and write about it so you can laugh, and think that maybe someday there will have been enough foreigners in this country that we cease to be as curious of an object as we are now.

deeper musings

Today was one of those days where almost nothing went right and instead of a mound of frustration and fruitlessness, I am left with the realization of how my patience and perspective have grown. Markedly. I have left the world of the instantaneous, and in many cases, the sensible, and slowly I am learning to function in the realm of the deliberate, and sometimes, the insane. I came to the Peace Corps with Dalai-Lama-esque ideals and thoughts of deep meditation and learning of values through local people. Instead I have stumbled upon a region that has been ransacked by communism and then hung to dry by a desire to be somewhere else, where life is easy and the money flows. Western desires meet communist tendencies. Greed takes over. Idealism is eclipsed by the need to put bread on the table. There has been way too much waiting and false promises—of new hope and a wealthy future. These people have to think critically and work together to get out of this situation and yet critical thinking and teamwork have been learned out of entire generations. Rote memorization is the rule here.

I do not want to waste my time or the time of others in a two-year stint on this side of the world. And I know that it is not a waste of my time, no matter how slowly things seem to move at times. The intellectual and spiritual growth afforded to me here is beyond compare. Never again will I have the time and opportunities that I have now. My reading and writing have never been as prolific, but I need to focus my energy. This is the contribution that Armenia makes to me—there is no cosmic teahouse, no Buddhist monks, the people themselves do not necessarily inspire me to greatness or any sort of transcendentalism. However, my position in this country and my ability to reflect on my American life from a new position and new perspective have granted to me that which I ultimately search.

In testing my patience on multiple levels, in the startling realizations of what post-soviet really means, in the daily struggle, in the rut of seed-chewing and squatting and cat-calling, in the everyday monotony and redundancy of a culture-deprived republic, where even the name of the culture house uses a Russian word, I have found new life in myself, and an ability to appreciate that which heretofore was simply too a minute a detail to have time for.

I want to be yogic, to be deliberate and meditative and peaceful. I have bought books and taken classes and filled my home with candles and plants and nice music, and now without candles or plants or even running hot water, I find that I have spent too much time trying and not enough time doing. I crave the comforts of home and then have to ask myself ‘why?’ Deprivation is an integral part of the PC experience. It is one of the reasons I came—a part of this existential quest. And desire is a part of deprivation, in fact it is definitive of deprivation—necessary for the full experience. But I have to ask what type of experience I am trying to cultivate, and further, why I can’t simply let this one be. Be. I need to be.

A strange lesson to learn from the country of Armenia, but perhaps the country isn’t important. PC is different everywhere, but is it the same too? Certainly it elicits similar feelings of hope, desire, frustration, gratitude, indulgence, martyrdom, fortitude and even defeat. There must be a greater sense of humanitarianism coupled with wanderlust. A strong recipe for self-improvement through introspection, or simply a clean slate. A new lens on life. And yet the first thing that comes flooding back is everything old. It clings to me, defines me. Nobody knows me—the old me—the only know the now me. And this only comes though observation as I stutter through “please pass the potatoes” at dinner. My actions are so important—they don’t require tenses or affixes or definite articles. Still, I am not totally understood and possibly I never will be. I have to take that chance. Besides, it isn’t what I am here for. My growth and that of my community will occur simultaneously and most likely neither will be very evident, perhaps for a very long time. This is one of the lessons of the Peace Corps—to be conscious of and happy with my own strides. It is possible I will be one of the only ones to notice, certainly the only one who truly knows the blood, sweat and tears behind even the mildest of accomplishments. Celebrate. Victories like this don’t happen every day, and like a stone in a pond, the ripples will continue—well after I have gone. At least I can hope.

This is the interconnectedness of our actions and in a deeper sense, it is why we are here as volunteers. We are the role models—for ourselves, for each other, for the countries we serve. It may take the countries a very long time to figure that out. That’s okay, our personal growth will surface more quickly, and this we will be able to apply to those things we interact with for a long time to come. This is the timelessness of the Peace Corps. An organization as effective in its own country as it is in those it services overseas. It is a thankless job. It is an important one. And it takes a certain strength of character and personal resolve to make it work, to get through the slow times, and to derive benefit from the most peculiar inanities of a foreign land.

I do not want to waste my time or the time of others in a two-year stint on this side of the world. And I know that it is not a waste of my time, no matter how slowly things seem to move at times. The intellectual and spiritual growth afforded to me here is beyond compare. Never again will I have the time and opportunities that I have now. My reading and writing have never been as prolific, but I need to focus my energy. This is the contribution that Armenia makes to me—there is no cosmic teahouse, no Buddhist monks, the people themselves do not necessarily inspire me to greatness or any sort of transcendentalism. However, my position in this country and my ability to reflect on my American life from a new position and new perspective have granted to me that which I ultimately search.

In testing my patience on multiple levels, in the startling realizations of what post-soviet really means, in the daily struggle, in the rut of seed-chewing and squatting and cat-calling, in the everyday monotony and redundancy of a culture-deprived republic, where even the name of the culture house uses a Russian word, I have found new life in myself, and an ability to appreciate that which heretofore was simply too a minute a detail to have time for.

I want to be yogic, to be deliberate and meditative and peaceful. I have bought books and taken classes and filled my home with candles and plants and nice music, and now without candles or plants or even running hot water, I find that I have spent too much time trying and not enough time doing. I crave the comforts of home and then have to ask myself ‘why?’ Deprivation is an integral part of the PC experience. It is one of the reasons I came—a part of this existential quest. And desire is a part of deprivation, in fact it is definitive of deprivation—necessary for the full experience. But I have to ask what type of experience I am trying to cultivate, and further, why I can’t simply let this one be. Be. I need to be.

A strange lesson to learn from the country of Armenia, but perhaps the country isn’t important. PC is different everywhere, but is it the same too? Certainly it elicits similar feelings of hope, desire, frustration, gratitude, indulgence, martyrdom, fortitude and even defeat. There must be a greater sense of humanitarianism coupled with wanderlust. A strong recipe for self-improvement through introspection, or simply a clean slate. A new lens on life. And yet the first thing that comes flooding back is everything old. It clings to me, defines me. Nobody knows me—the old me—the only know the now me. And this only comes though observation as I stutter through “please pass the potatoes” at dinner. My actions are so important—they don’t require tenses or affixes or definite articles. Still, I am not totally understood and possibly I never will be. I have to take that chance. Besides, it isn’t what I am here for. My growth and that of my community will occur simultaneously and most likely neither will be very evident, perhaps for a very long time. This is one of the lessons of the Peace Corps—to be conscious of and happy with my own strides. It is possible I will be one of the only ones to notice, certainly the only one who truly knows the blood, sweat and tears behind even the mildest of accomplishments. Celebrate. Victories like this don’t happen every day, and like a stone in a pond, the ripples will continue—well after I have gone. At least I can hope.

This is the interconnectedness of our actions and in a deeper sense, it is why we are here as volunteers. We are the role models—for ourselves, for each other, for the countries we serve. It may take the countries a very long time to figure that out. That’s okay, our personal growth will surface more quickly, and this we will be able to apply to those things we interact with for a long time to come. This is the timelessness of the Peace Corps. An organization as effective in its own country as it is in those it services overseas. It is a thankless job. It is an important one. And it takes a certain strength of character and personal resolve to make it work, to get through the slow times, and to derive benefit from the most peculiar inanities of a foreign land.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)